Julia kobelt: Marine Scientist Research Technician and activist

Tell us about yourself! When did you start diving or get involved in ocean science?

I grew up far from the ocean in Wisconsin, but always had a passion for biology and ecology. My first marine science experience was in spring 2015 at Friday Harbor Labs, the University of Washington’s marine biology field station. I took the marine invertebrate zoology/marine botany (“Zoo-Bot”) class which involved a lot of time among the rocky intertidal zone and examining live organisms under the microscope. I was blown away by the quirkiness of marine invertebrates, the beauty and complexity of algae, and the ecological processes that connected them. I was eager to see more, so I started diving that fall and became an AAUS scientific diver in summer of 2016.

On a personal note, I love cooking, live music (back when that was a thing), and care deeply about political activism.

Can you share more about your work?

I am a research technician working with Aaron Galloway (U of Oregon) and the Nature Conservancy. We are part of a larger research team studying sunflower star ecology, which also involves studying sea urchins and kelp.

Sea urchins are notoriously hungry herbivores, and when urchin populations get too large they can destroy kelp forests by eating all of the kelp and preventing new kelp from growing. Predators including sunflower sea stars (Pycnopodia helianthoides) keep urchin populations under control which can help kelp forests thrive.

In recent years, sunflower stars have almost entirely disappeared due to Sea Star Wasting Disease. And since then, scientists have observed exploding sea urchin populations and massive declines in kelp. Given these dramatic changes, it is important now more than ever to understand the role of sunflower stars in kelp forest ecosystems.

I am part of a research team studying sunflower star ecology, with a goal of linking the recovery of sunflower star populations to kelp forest restoration. Last summer, we studied one of the few remaining populations of sunflower stars on the West coast, in the San Juan Islands. We did some lab experiments at Friday Harbor Labs to study how sunflower stars interact with sea urchins, including how many urchins they can eat per day and how the starvation state of the sea urchins affects their interactions with the stars.

Sunflower stars are a favorite amongst some of our team. We watched them dissolve before our eyes in Edmonds. How can divers interested in science count and record sunflower stars for scientists?

Since sunflower stars are so rare now, it is difficult to accurately count them with traditional survey methods like transects or quadrats. Instead, my research group has been using a metric called “catch per unit effort” to estimate star population size. It’s commonly used in fisheries research and basically measures how many individuals you see (“catch”) over the time you searched (“effort”). Divers can record how many stars they saw, size (relative to your hand), depth, and bottom time of the dive. For example, you could report 1 medium star (the same size as your hand) at 10m depth, over a 30-minute dive.

How did you become interested in sea urchins, sea stars and kelp forest ecology?

I began my marine science career studying sea urchin poop! Urchins are quite inefficient at digesting food and leave behind loads of partially digested kelp scraps in their poop… so I studied how sea urchin poop fits into the marine food web. I wanted to know: Is digested kelp (urchin poop) more nutritious than fresh kelp? Turns out urchin poop is better food, and may be an important way of moving nutrients through the food web.

I also worked as a marine technician at FHL for a year after graduating from UW, where I continued studying sea urchin digestion. As a resident scientific diver at the labs, I also got to help out with many subtidal research projects including bull kelp (Nereocystis luetkeana) field experiments in the San Juan Islands. Diving in kelp forests and seeing all of the diverse life they support really solidified my love for kelp forest ecology.

What do you think everyone should know about sea stars?

Have you ever seen a sea star with different sized arms? If a star is damaged, or drops an arm to escape a predator, they can completely regenerate it. And sometimes a whole new star can grow from a single arm! During the lopsided regrowth period, we call these stars a “comet.”

With your work, what do you hope to accomplish?

Kelp forests are one of the most diverse and productive ecosystems on the planet. Kelp provides habitat and food to countless species, absorbs more carbon from the atmosphere than a terrestrial forest, and protects our shorelines from erosion. We are losing kelp at unprecedented rates, and we need to act fast to understand how we can conserve them.

My research is just one part of a larger effort to study the impacts of the loss of predatory sunflower stars on marine ecosystems, and how we can help their populations recover. Our Pycnopodia Recovery Working Group is looking at everything from breeding sunflower stars in captivity, to measuring the genetic diversity of the remaining wild sunflower star populations. We hope that restoring sunflower star populations will bring stability to kelp forest ecosystems, and keep urchin populations under control. Restoring the predator-prey balance in kelp forest ecosystems can protect the ecosystem against devastation from future changes like ocean warming or new marine disease epidemics.

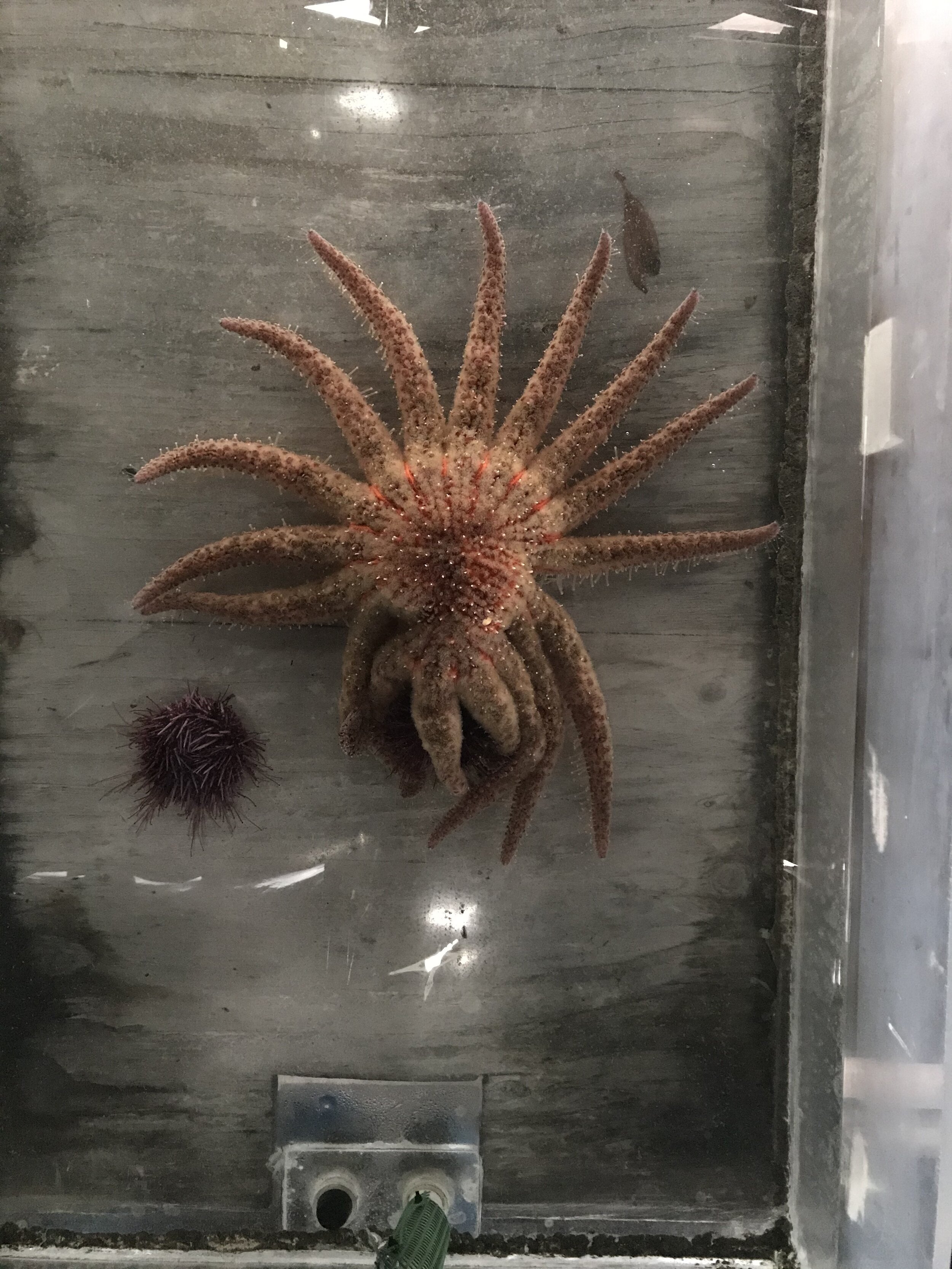

Sea urchin defending itself against sea star attacks.

What was some of the best advice you have received from mentors...and/or what advice do you have for young scientists, artists and explorers? Or Both!

Get comfortable with being uncomfortable! It can be scary, but the greatest personal growth will happen when you push yourself out of your comfort zone and take advantage of opportunities to try new things.

Please share a favorite memory from your work or from a dive?

Watching the sunflower stars and sea urchins interact during the experiments was so much fun! I learned that urchins will defend themselves against sea star attacks with their pedicellaria, which are tiny venomous pinchers that cover their body in between the spines. It was fascinating to see the variation in how bold and aggressive the stars are - some stars will run away from the urchin’s pinches, while other stars will keep attacking.

Thank you for sharing with us! Keep inspiring others with your research and activism. Check out Julia’s page.

We always love to be introduced to new ocean explorers. If there’s someone you’d like to see an interview from, send us your ideas!